Phone

+90 532 203 7931A Patient's Perspective: John's Chance Discovery On the Surgical Table

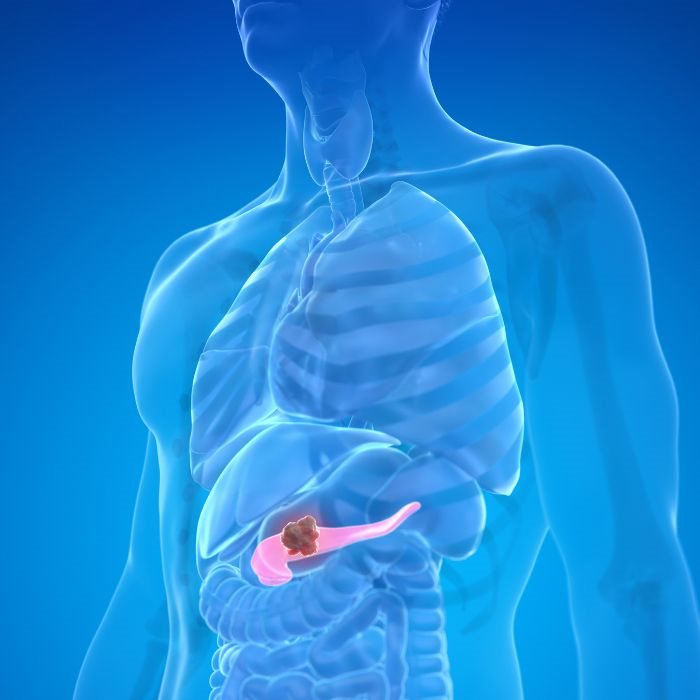

John is a 60-year-old accountant. The finding was made during a routine check-up. What was bad news soon became much worse: when his doctors looked at the images, they stated, "A tumor such as this one appears to have invaded several major blood vessels which are, from the looks of it, the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and the portal vein." This meant that his cancer might be inoperable, and this grim reality left John feeling hopeless.

But John's story really took an unexpected turn in the operating room. In surgery, his doctors found out that, contrary to what the imaging had said, the tumor had not really invaded the blood vessels. The surgical team could actually remove the tumor completely, giving John the fighting chance that imaging alone did not give.

John's experience underscores a central dilemma of pancreatic cancer: the relationship between what radiological imaging shows and what surgeons find once they are in. This article takes us through the topic and discussion arising out of this: how imaging sometimes lies, and why such is both a matter of criticism and exhilaration: for patients generally, and conversing with their physicians.

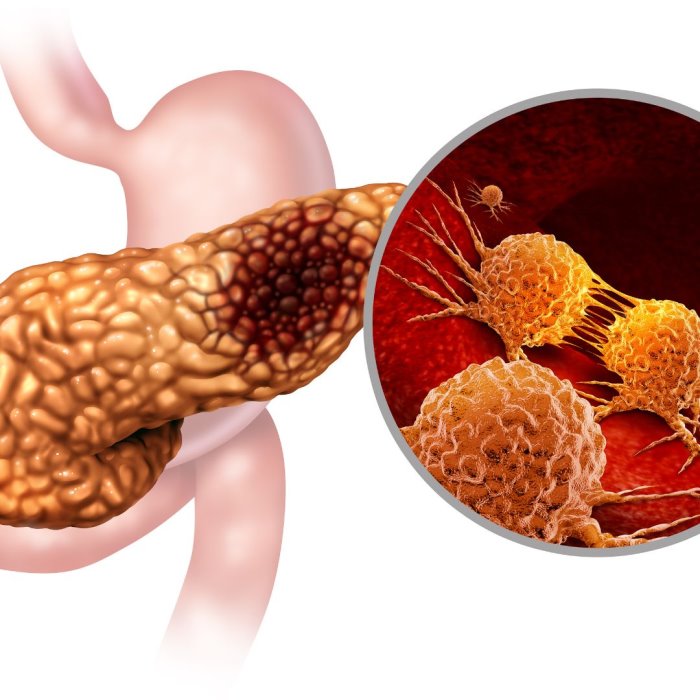

The Fact and Fancy of Radiology in Pancreatic Cancer

Radiological imaging has a primary role in the diagnosis and in planning treatment for pancreatic cancer. The common imaging techniques done in this context include computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and Doppler ultrasound. They help in establishing size, location, and extent of tumors and their relation to neighboring structures, including the blood vessels.

For example, CT scans provide detailed cross-sectional images where the physician can evaluate how close the tumor lies to important vessels. MRI allows better contrast in soft tissues, and hence, it is able to pick up minor changes in the pancreas and surrounding tissues. The Doppler ultrasound evaluates blood flow and helps to identify any impingement of or invasion by a tumor on blood vessels.

These imaging techniques facilitate the staging of pancreatic cancer to determine whether the disease is localized, locally advanced, or metastatic. The results on these scans determine the management, in fact the possibility of surgical resection. However, for all their advancement, imaging techniques are not foolproof, and this is exactly where the problem arises.

The Discrepancy: Imaging vs. Surgical Findings

The greatest challenge in treatment of pancreatic cancer comes with the discrepancy between what imaging suggests and that which surgeons encounter during operation. It turned out that up to 85 % of the cases in which imaging indicated vascular invasion did not actually invade the blood vessels upon surgically checking them. This discrepancy has profound implications for the treatment decisions and patient outcomes.

Although the imaging is high level, sometimes it overestimates the tumor involvement with blood vessels. It happens mainly for a couple of reasons. One is that the pancreas lying on a dense fibrous tissue does not allow it to move freely. A shadow in some scans may direct the appearance, such as that within the vasculature. However, the tumor is adjacent to vasculature but not invading it. As a result, there was not the appropriate resolution of imaging for separation of true invasion from proximity.

This means that, with such a difference in imaging, one can consider a patient's cancer as unresectable, although this is absolutely not the case and such a patient can still be salvaged through surgery for possible cure. Thus, a patient who could be treated with a curative intent would instead be given palliative therapy. At this point, it becomes important to know and consider the constraining factors in the imaging and to follow a multidisciplinary approach which would also consider the views of experienced surgeons.

Why This Discrepancy Matters: Impact of Treatment

But this is more than just a technical discrepancy: this affects real patients and their treatments. Common classification for surgery is 'unresectable' if a tumor is suspected to have invaded major blood vessels according to imaging findings. This is important because patients may possibly be condemned to chemotherapy, radiation, palliative care, or just a few more months of life when they could have been cured by surgery.

This paradox is often a reality discovered at surgery; that when there is no actual vascular invasion then a patient will indeed be technically suitable for surgical resection and therefore the possibility of cure for pancreatic cancer—the only chance of cure for pancreatic cancer. This inconsistency underscores the fact that imaging alone is an unsatisfactory basis for treatment or non-treatment decisions. Take home point; that imaging suggesting a cancer is unresectable does not obviate the need for careful surgical exploration.

This should therefore mean that for patients, a diagnosis of vascular invasion from imaging should not be taken as an absolute end to surgical options. Instead, it should be one component of consideration that the possibility for the reevaluation of the surgery has not been excluded. This broadens the spectrum of other treatment possibilities and, in the long run, maximizes the benefit.

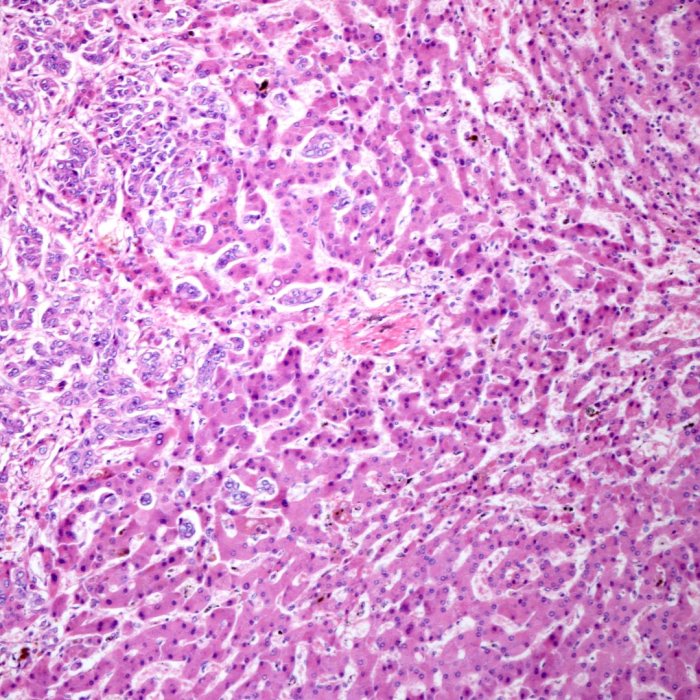

Research Supporting the Discrepancy

The phenomenon of overrating vascular invasion in pancreatic cancer is well documented by a plethora of studies in medical literature. A lot of research work has been carried out dealing with the sensitivity of CT, MRI, and other imaging in the prediction of vascular involvement, and the results consistently show a significant level of false positivity.

For instance, in a study conducted in *Annals of Surgery*, it has been reported that during surgery, not more than 15% of patients with supposed imaging-indicated vascular invasion had an actual invasion. Another research work published in *Pancreas* has pointed out that imaging sensitivity in the detection of real vascular invasion is poor, thus probably leading to a misclassification of disease stage.

These findings fueled the current awareness that resectability cannot be determined by imaging alone. Imaging results should be taken into perspective, and other factors like experience and judgement by the surgical team have roles in deciding for surgery. This can avoid the unnecessary exclusion of patients who could benefit from the potentially life-saving benefits of surgery.

Building Hope: With an Otherwise Bleak Summer Sky

Although this discrepancy between imaging and surgical findings can be frustrating, it also carries a silver lining of hope. For patients who are initially told their cancer was inoperable due to vascular invasion, surgery is possible and may convert a potential dead end to a diagnosis that carries further potential in the patient's treatment plan.

Bottom line for the patient and clinician: Imaging is not the last word. Surgical exploration is important in the process of treating pancreatic cancers, and overreliance on imaging in making decisions on such a matter could be disastrous. Realizing its limits and keeping the ever-open possibility of reevaluation of surgical candidacy might allow access to treatments thought impossible to attain.

Reiterating the above further, the crack underscores the message of a multi-disciplinary modality of cancer care. To interpret the imaging findings and decide on the best treatment options, one would need to work among surgeons, radiologists, and oncologists, taking into account every detail of the patient's case. This can translate into more accurate staging, better planning treatment, and better outcomes.

Navigating Pancreatic Cancer with Knowledge and Hope

Pancreatic cancer is a very challenging disease, which further aggravates with the issue of vascular invasion. Though radiological imaging is necessary both for the diagnosis and staging of this cancer, it is not free from its potential pitfalls. The disagreement between that shown by imaging and that present at operation demands some caution in reading, as well as for treatment decisions.

To John, and all of his patients: it will mean the difference between a diagnosis of cancer-incurable, or a chance for curative surgery. In this way, knowing when imaging has its limits and when surgical exploration is called for averts hope being dismissed where it seems there cannot be any.

As we continue to advance our understanding of pancreatic cancer and make improvements to our diagnostics, the goal remains—every patient receives the most accurate diagnosis and the best possible care he or she deserves. By challenging common misconceptions, such as taking a multidisciplinary approach, we would take a leap in between the complexities that tag along with pancreatic cancer with knowledge and hope.